During the darkest days of lockdown, Atalanta captain Papu Gomez described living in Bergamo as "like being in a horror movie". The Argentine insisted, "I’m not exaggerating." And he wasn't.

On March 18, just eight days after Atalanta had qualified for the quarter-finals of the Champions League for the first time in their history, military trucks snaked through the deserted streets of Bergamo to collect coffins. The city's morgues and churches had been overwhelmed.

At the time, an average of more than 40 people were dying every day in Bergamo. The city was morbidly nicknamed 'Italy's Wuhan' – a reference to the Chinese province which had experienced the first major outbreak of the virus.

The majority of the pages in the local newspaper, L’Eco di Bergamo, were dedicated to obituaries.

As Italy shut down and strictly enforced social distancing rules, some families were separated. Others were prevented from saying goodbye to their mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, sons and daughters.

Given the way in which the virus prayed on the elderly, an entire generation was lost; whole communities devastated.

What many found so hard to take was that some deaths were avoidable. The perils of the pandemic had undoubtedly been underestimated by some governments and ministers. Football's authorities were culpable in that regard too.

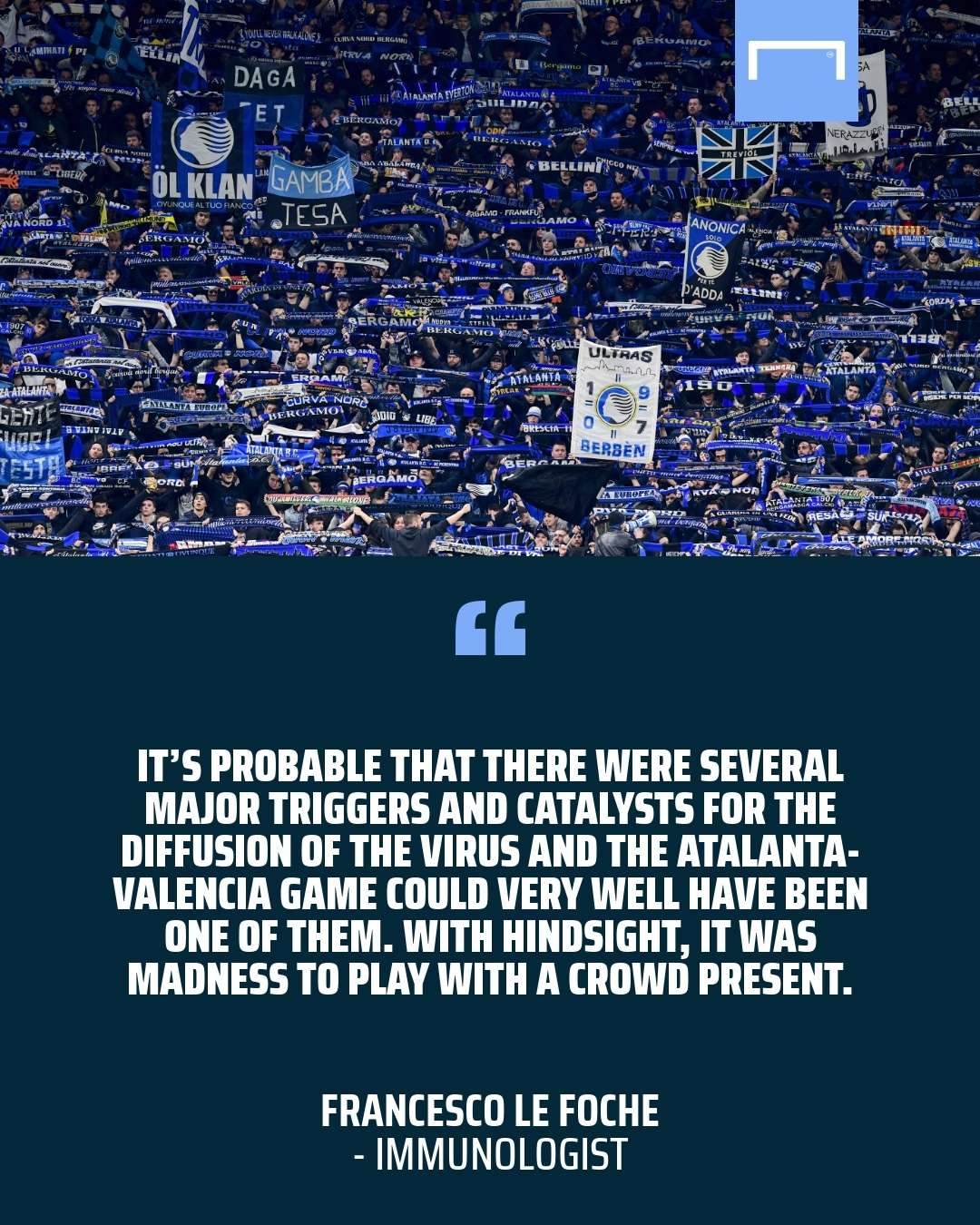

On February 19, Atalanta played Valencia at San Siro. More than 40,000 Bergamaschi had travelled down to Milan for the first leg of the Champions League last-16 tie. Or what would later become known as 'Partita Zero' ('Game Zero').

Getty Images

Getty Images

The mayor of Bergamo, Giorgio Gori, has also described it as a "biological bomb", with immunologist Francesco Le Foche telling the Corriere dello Sport: "It’s probable that there were several major triggers and catalysts for the diffusion of the virus and the Atalanta-Valencia game could very well have been one of them.

"The aggregation of thousands of people, centimetres from each other, engaging in manifestations of euphoria like hugging, shouting, all of that could’ve favoured viral reciprocation.

"With hindsight, it was madness to play with a crowd present."

The return fixture was played behind closed doors on March 10, but even that was folly. Even aside from the fact that Valencia fans gathered outside the Mestalla, the Spanish club revealed after the second leg that "around 35 per cent" of its players and staff had contracted the virus.

Atalanta coach Gian Piero Gasperini also later admitted that he had been suffering from extreme flu-like symptoms at the time and later tested positive.

"We all underestimated it," defender Robin Gosens confessed to Gazzetta dello Sport. "I was the first. I told myself that it was at best a flu. I went out, went to the restaurants, met my friends.

"We didn’t know about this enemy and the capacity of it. We understood it only when there were already many cases."

Indeed, it was only when Gasperini's squad arrived back in Bergamo from Valencia that they realised their entire world had changed. They returned to a very different city to the one they had left behind.

“We have plunged into a reality that we knew was terrible, but not at this point," Gasperini said on March 12. “We have no idea about the future. Only uncertainties."

Worse was to follow. At the very peak of the pandemic in Italy, just under 1,000 people were dying on a daily basis.

Getty Images

Getty Images

However, from March onwards, a nation united in its fight against the spread of the virus. Medical staff led from the front but nearly every person across the country played their part by following the guidelines.

In Bergamo, Papu and his team-mates played their own small part by urging people to respect the lockdown rules.

"I tell all the runners, or fake runners, who want to still go out and train, stay at home,” the captain wrote on Instagram. “Enough, enough, enough!

"Every morning we wake up to bad news, people are dying, and you still don’t realise? Everyone at home, nobody must go out."

And it is thanks to such pleas from people from every walk of life that Italy has now returned to something resembling normality.

Shops, bars and restaurants have reopened, with people adhering to the social distancing instructions and obligations to wear a mask in certain situations.

Football has returned too and Atalanta, perhaps unsurprisingly, are playing with an even greater passion than ever before.

The club with the 13th-biggest wage bill in Italy has, remarkably, sealed a place in the Champions League for the second successive year courtesy of a third-placed finish in Serie A, with a club-record points haul.

Now, though, they are eyeing a place in the semi-finals of this season's competition.

On Wednesday, they will face Paris Saint-Germain in a one-off knockout game in Lisbon. PSG, with their superstar squad, are, of course, the favourites to progress.

However, Atalanta are cautiously optimistic about their chances. They believe in their coach and his tactics. But they also believe that this is their destiny; their obligation to their traumatised city.

Football played a part in the devastation in Bergamo; but it's also playing a part in the healing process.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Just before the resumption of play, Gasperini told the Gazzetta: "Bergamo is suffering from a deep sadness that you can feel everywhere, in the streets, in the eyes of the people, in the bars and in the restaurants, in the silences of my staff member who lost his father.

"Everyone is going forward, with strength but with intense pain. It will take years to fully comprehend what happened here, because this was truly the centre of the hurt.

"Every time that I think about it, it feels absurd: the historic peak of sporting joy coincided with the city's greatest pain.

"I've been asked many times if it's right to return. Some consider it 'amoral'. But I've seen people singing from their balconies in Italy while trucks were collecting the dead in Bergamo and I don't consider that 'amoral'.

"I consider it an instinctive human reaction, an attempt to embrace life, to react to tragedy.

"Atalanta can help Bergamo start again, after all of the pain and the mourning. The team has always remained connected to Bergamo and its suffering. And we will take it on to the field."

Bergamo’s veritable horror story deserves something resembling a happy ending. An Atalanta victory over PSG would certainly help.

"We wouldn't just like it," Gori wrote in the Gazzetta. "Maybe we need it a little bit too..."