“I'm sorry, what do you want me to do about it? I'm the 'Messiah', but I don't perform miracles. That's life.”

Jair Bolsonaro's callous response to Brazil passing 5,000 coronavirus deaths caused outrage both locally and across the world. Cases and fatalities in the nation continue to escalate daily and now stand at over 12,000, but he continues to play down the severity of a disease which has brought the world to a halt.

Following the example of his professed mentor Donald Trump – United States flags are a regular fixture at the public rallies he continues to hold despite public health warnings – Bolsonaro is hell-bent on restoring 'normality', even while the health system creaks under the strain of more than 170,000 confirmed Covid-19 cases. Football forms a key part of that strategy, meaning clubs and players are being forced to return to activity with minimal guarantees over safety.

The game came to a halt in Brazil following the weekend of March 16, halfway through the myriad state championships which, from Amazonas to Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo, form the traditional curtain-raiser to the season's calendar. Last week marked the return of the first teams to training, with Porto Alegre giants Gremio and Internacional both going through their paces.

For those players reluctant to put their health in jeopardy, Inter president Marcelo Medeiros presented a simple, if rather unhappy solution. “I am sure everyone wants to work. Another problem we are facing now is the economic issue. Those players who don't want to play can quit,” he fired to Radio Guaiba.

Next Match

“If the chance to bring football back comes up, [each player] will respect the contract he has signed.”

In any event, the two rivals' comebacks proved brief, lasting just four days. On Sunday the Rio Grande do Sul state government banned training, after learning that coronavirus tests held for Gremio players returned three positives.

A similar cloud was cast over Rio de Janeiro side Flamengo, who lost their veteran masseur of 40 years Jorginho to the virus; 293 players, coaches, family members and employees were tested, of whom no fewer than 38 came back positive.

It was Gremio who first brought to light the need to halt football, when on March 15 they took the field donning surgical masks in a protest against authorities' decision to keep the ball rolling. The Tricolor's actions provoked the wrath of the president, who at every step has gone to great lengths to proclaim business as usual in Brazil. Bolsonaro has never been in agreement with the sport's suspension and sees it as an essential service that must be set free as soon as possible.

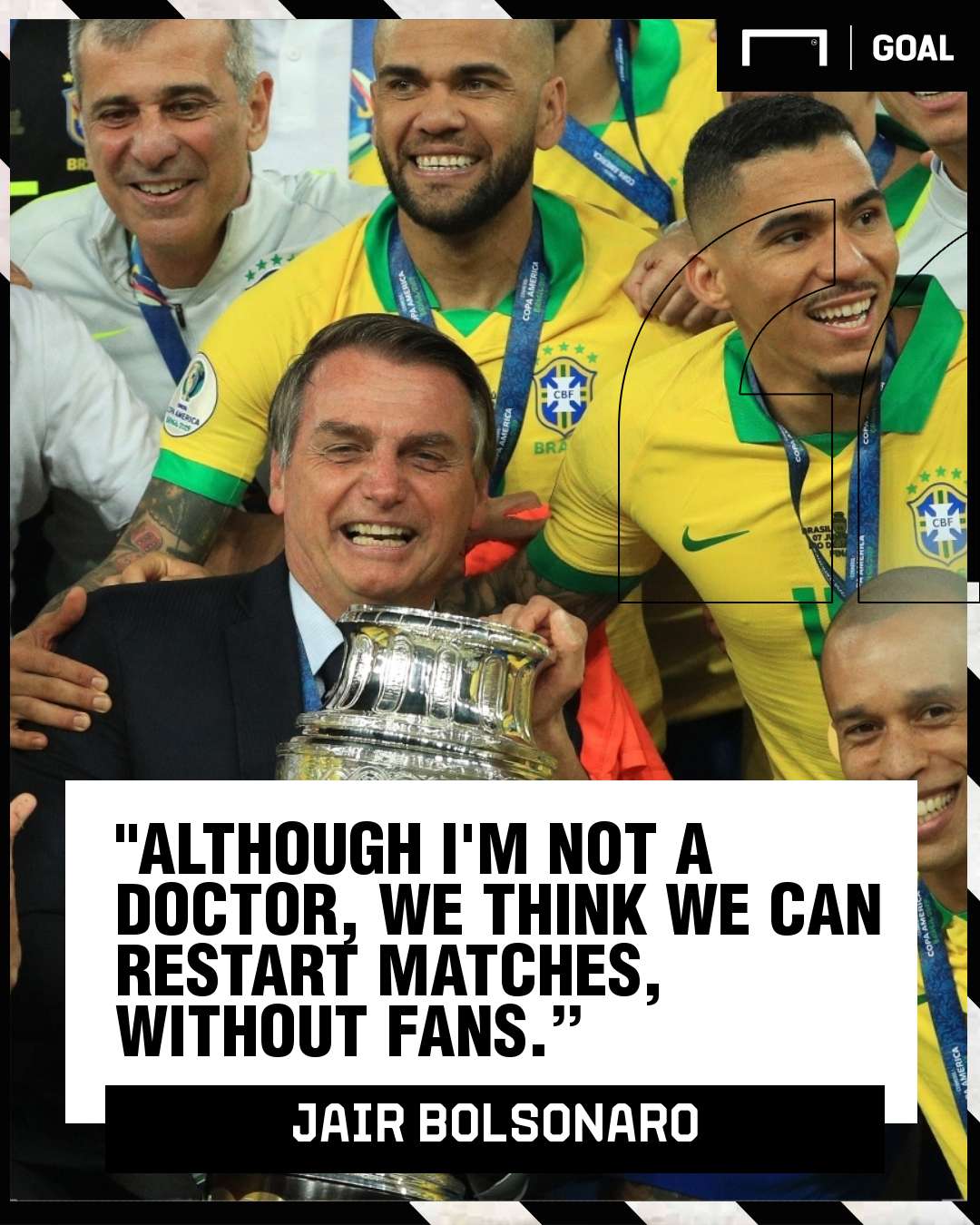

“To our understanding, and although I am not a doctor, we think we can restart matches, without fans at the start,” Bolsonaro had urged as recently as Friday. This new setback must surely end such a notion, at the very least until infection rates in Brazil begin to slow. However, as he has shown throughout his presidency, the head of state is not one to take kindly to his will being thwarted.

Football has every reason to fear the next move from a man who has already fired his health minister during the pandemic for refusing to defend his insistence on avoiding lockdown, and whose demands to open up the sport again met, in almost every case, with sullen silence from clubs, directors and players.

As the scale of the disaster nationwide becomes evermore apparent, that silence is slowly being broken. On Tuesday, the same day that Brazil announced 881 deaths in 24 hours – a new record – two prominent figures spoke out against the notion of bringing football back.

“With all due respect, coming back in the way that some teams are doing it is unacceptable. Ten metres distance, wearing masks... it is better not to go back than that,” Corinthians president Andres Sanchez affirmed in a web interview. Ceara goalkeeper Fernando Prass went even further telling reporters: “In Rio Grande do Sul, which has 10 times fewer deaths than Ceara, the clubs came back and now training has been banned again.

“So how can the government be in favour of football coming back? It is a rather strange thing and, in my opinion, insane.”

Judging by the public outbursts of its head of state and the actions of many of his supporters, this is beginning to look like the new normal for Brazil, as tragedy continues to mount in the wake of Bolsonaro's stubbornness.

Bringing football back against such a backdrop of overloaded hospitals, hastily-dug mass graves - as have been seen in cities such as Manaus - and warnings that the situation in the nation's favelas and poorest regions is already verging on the catastrophic would not just be irresponsible – it would be outrageous.