Former UEFA chief executive Gerhard Aigner once dismissed the potential for a European Super League as "an illusion" – but its power is very real.

In August 1998, a group of unexpected visitors turned up at Lenart Johansson's holiday home in Switzerland.

Representatives from Media Partners, the Italian conglomerate, surprised the UEFA president with a bold proposal for the launch of a new competition for Europe's top clubs backed by Rupert Murdoch, Silvio Berlusconi, Leo Kirch and Prince Al-Waleed bin Talal.

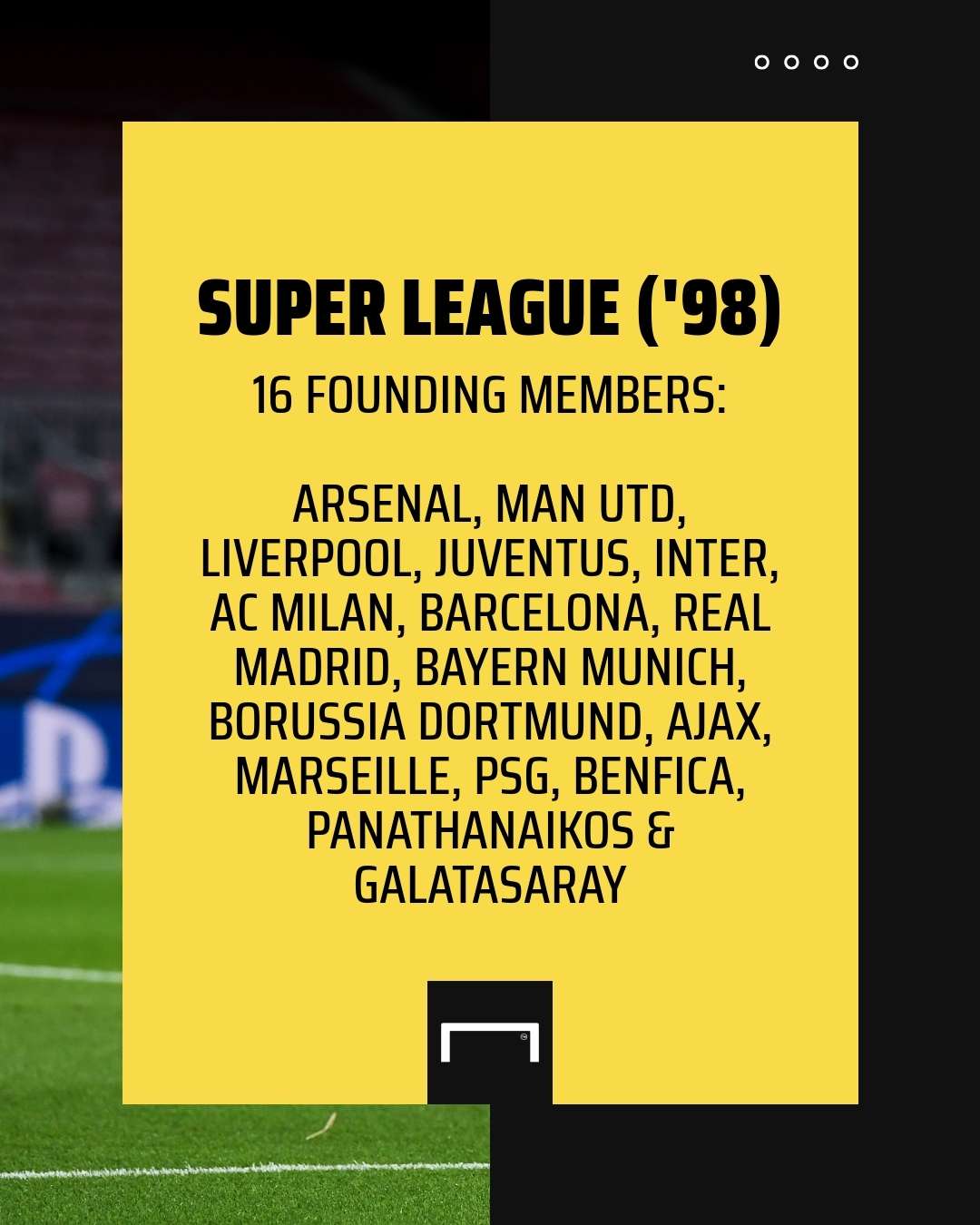

Their 'Super League' would consist of 32 teams, including 16 founder members who would be guaranteed participation for at least the first three seasons.

The participants would be split into two divisions and would play 15 games per season, facing each team in their division home or away – but not both.

The top eight clubs in each division at the end of the regular season would then enter a knockout stage or round-robin tournament to determine a champion.

Media Partners claimed that the participants would receive, on average, £16.8 million ($22.8m) – before prize money was even taken into account. To put that in context, Manchester United had earned only £6.5m ($8.8m) from reaching the quarter-finals of the previous season's Champions League.

The 1998 Super League proposal was dismissed by UEFA but, tellingly, the Champions League was increased from 55 teams to 71 just two years later, allowing up to four teams from Europe's biggest countries to enter for the first time, while more games were created with the addition of a second group stage.

Consequently, that summer's day in Switzerland would be the last time anyone in football was ever again taken by surprise by the threat of a Super League. It returns, regular as clockwork, every single time Europe's biggest and richest clubs have a grievance with the governance of the game.

"And the threat of a Super League always ends with UEFA promising the big clubs more revenue, " Tsjalle van der Burg, an assistant professor in Economics at the University of Twente, tells Goal.

"As long as UEFA is doing that, there will be no Super League. However, by constantly meeting the big clubs' demands because of the threats, we will end up with a format that closely resembles a Super League."

Getty/Goal

Getty/Goal

Thus, the re-emergence of Super League speculation at the tail end of 2020 was entirely expected. The current agreement on the international match calendar will expire in 2024, meaning there is scope for restructuring the continental club game, and preliminary talks among the game's major stakeholders are already under way.

The future format of UEFA's flagship event, the Champions League, is understandably drawing much of the media and fan focus. Will the group stage be expanded in 2024? Will the qualification process change? Will certain clubs be guaranteed participation?

These are all valid and fascinating questions, and the answers will have a massive impact on European football as a whole. However, of even greater significance will be the decision taken on the distribution of UEFA Club Competitions (UCC) revenue. As Goal has learned, UEFA will discuss the matter in talks with some of the game's stakeholders later this week.

Football has experienced rapid financial growth over the past decade and the gap between Europe's richest and poor clubs is not just increasing – it is accelerating at a rapid rate.

The size of a club's coffers is influenced by three primary revenue streams: its domestic league's broadcasting deal, its own commercial contracts, and UCC money.

Sponsorship deals are obviously important and influential. United, for example, may not have enjoyed much on-field success since Sir Alex Ferguson's retirement in 2013, but they remain a commercial colossus due to their global appeal and make millions from partnership deals.

The significance of TV money cannot be overstated either. One only has to look at the wealth of the Premier League to see evidence of the incredible effect rights deals can have on a domestic competition.

As pointed out in the European Leagues' study 'The Financial Landscape of European Football', a quarter of all expenditure on broadcast content in Europe is allocated to football. We are clearly no longer talking about the people's game, then, but a lucrative entertainment industry.

However, the area which has experienced the biggest growth over the past 10 years is UCC distributions.

Getty/Goal

Getty/Goal

"European fixtures are already the biggest distortive factor in the competitiveness of domestic competitions, including the Premier League," Kevin Miles, chief executive of the Football Supporters' Association (FSA), tells Goal.

"The Premier League has a distribution model which has been relatively flat, with relatively being the key word. A big chunk of their money is shared out equally. You then have the competition prize money, which is determined by where you finish in the league. However, there was an element of the wealth being shared among all the clubs, and an element of solidarity with the rest of the pyramid.

"But every time there is a proposal for a European Super League and it gets knocked back, there follows an appeasing adjustment in the Premier League in favour of the biggest clubs. The last time it happened, there was a change in the distribution of international broadcasting rights revenue. So, a bigger proportion went to the big clubs.

"With this latest threat, what we're likely to see is a reduction in the size of the Premier League, from 20 teams to 18 or even 16, meaning fewer domestic games but more space for European fixtures, which will only shift the balance even more in favour of those playing in UEFA competitions."

Indeed, the top three clubs in each of the 'Big Five' European leagues accounted for, on average, 85 per cent of the revenue their country received during the previous UCC cycle (2015-18). In short, increasing sums of money are going to a decreasing number of clubs.

With the rich getting richer, it is becoming ever more difficult for the poorer clubs to qualify for the Champions League, which means they are only falling further behind. It is a vicious cycle that will mean only a small group of teams will soon be able to compete for domestic and European trophies.

One of the biggest arguments against a Super League is, as UEFA themselves have claimed, that a closed-off competition devoid of promotion and relegation would be "boring". However, we are already in danger of reaching that point within the existing framework.

Sport retains its ability to surprise, of course – Leicester City in England and Atalanta in Italy provide recent evidence of that – while it must be acknowledged some clubs and indeed leagues are simply bigger than others for historical reasons that are rooted in cultural and socio-economic factors.

However, there is clearly something very wrong with the system when one considers that Paris Saint-Germain have won seven of the past eight Ligue 1 titles, Bayern Munich are on course for a ninth consecutive Bundesliga crown, and Juventus are looking to make it 10 Scudetti in a row in Serie A.

Getty/Goal

Getty/Goal

Even the supposedly uber-competitive Premier League is experiencing worrying trends. Leicester pulled off a miracle by winning the title in 2016, but Manchester City and Liverpool have since made 90-plus points hauls the norm for a championship-winning side.

As La Liga president Javier Tebas has argued in the past, the problem is not that big teams have continued winning titles over the past 10 years – but how they are winning those titles.

Records are falling at a ridiculous rate. During the past decade, we have seen teams win leagues with 100 points or more in Italy, England and Spain. Smaller clubs are being reduced to also-rans.

It has taken a pandemic to level the playing field somewhat. Even Europe's elite have been affected by the financial crisis caused by the Covid-19 outbreak – Barcelona are flirting with bankruptcy while Real Madrid did not spend a cent last summer – and the congested fixture list has resulted in numerous injuries and widespread fatigue.

As a result, we are seeing bizarre results and tighter title races in leagues that have been dominated by one super-club for the past decade. This apparent equality will not last, though. Particularly as the pandemic has only panicked the game's top clubs.

It has accelerated their need for stability and certainty. The European Club Association (ECA) is pushing hard for Champions League reform because its members want more guarantees and less unpredictability. So, while the latest Super League chatter may have upset football fans, it was welcomed by Juventus and ECA chairman Andrea Agnelli and those he represents. In a way, the fan backlash suits UEFA too.

They may be forced to cede to more requests from the clubs than they would like, but when an agreement is eventually reached over the reformation of the Champions League – and it surely will be – president Aleksander Ceferin will still be able to boast about having staved off the threat of a Super League once again.

Getty/Goal

Getty/Goal

However, the revamped Champions League could still retain most of the Super League's proposed elements: an expanded group stage and qualification based on historical results rather than pure sporting merit.

What is absolutely essential, then, is that UEFA also endeavours to protect the rest of Europe's clubs – and not just those competing in its continental competitions.

UCC distribution money may have increased enormously over the past 10 years, but solidarity payments have fallen behind and, thus, remain relatively small.

The amount of money UEFA distributes to every national association is determined by a variety of factors. For example, countries which had a representative in the Champions League group stage receive a higher figure.

Generally, this money is shared among the 650 or so clubs who did not play in the group stage of either the Champions League (32) or the Europa League (48) and, between 2009 and 2018, non-participating solidarity payments grew in line with UCC payments.

However, a new three-year broadcasting cycle began ahead of the 2018-19 season, which resulted in a massive divergence and saw Champions League and European League payments increase by 50%, but solidarity payments grow by just 20%.

Consequently, we now find ourselves in a situation where 93% of UCC club distributions are being shared between Champions League (80%) and Europa League participants (20%), with the remaining 7% being split between teams eliminated in the qualifying rounds and those that did not participate at all.

With a new cycle set to begin, there is a very real danger that the goalposts are set to be moved again, and the 650 clubs not competing in Europe will receive an even smaller slice of the pie, meaning if a team is not regularly competing in the Champions League, it will have little chance of competing at all.

The counter-argument will be, of course, that the Europa Conference League is being introduced for the benefit of smaller clubs. However, many questions remain unanswered at the time of writing.

Getty/Goal

Getty/Goal

As Kieran Maguire, author of 'The Price of Football', tells Goal, "UEFA have been very quiet about distribution payments from next season, particularly in relation to the Conference. I can't see the big clubs in the Champions League being willing to give up any of the money they earn from their 80 per cent share of UCC revenue.

"So, where will the money for the Conference come from? Will it come from UEFA's coffers? Is it supposed to be self-financing? Because the broadcasters I've spoken to certainly aren't interested in the tournament. It's a glorified version of the EFL Trophy!"

The purpose of the Europa Conference League is to appease and generate money for the biggest clubs in Europe's smaller leagues, but this is not an adequate solution to financial inequality. Qualifying round payments are already having just as big a distortive effect on smaller leagues as Champions League participation within the 'Big Five' leagues.

And competitive balance is suffering as a consequence, with the same teams winning titles every year now, and often by record-breaking margins.

What happens next, then, is absolutely crucial to the future of football. It is essential that all clubs are looked after, and that all voices are heard. UEFA must listen to the fans, as well as the clubs, leagues and broadcasters.

UEFA could also do with some help and Van der Burg believes that the European Union (EU) could remove the threat of a Super League once and for all, thus allowing the governing body to focus solely on reform.

"My view is that the Super League itself, and the threats of a Super League, are incompatible with Article 101 of the EU's competition law,” says Van der Burg, who has written a paper on the matter. "So, the EU should tell the football sector that it doesn’t want any more threats of a breakaway.

"By removing those threats, UEFA’s full power would be restored, allowing it to follow through on Ceferin’s stated goal of improving the competitive balance in European football. Doing so would make the present format more interesting to the fans again, which, in turn, would end the possibility of the Super League becoming a more appealing system than the current one."

A decision on UCC revenue distribution for the next cycle, between 2021 and 2024, is expected to be made by the summer and, significantly, European Leagues have asked that UEFA doubles solidarity payments for non-participating clubs to 8% – a request backed by the majority of clubs and fans across Europe.

UEFA's response, then, will provide us with a clear indicator of the direction in which the game is headed.

If no attempt is made to reverse – or at least halt – the current rate of divergence between UCC distribution money and solidarity payments, we will know that some clubs and leagues will be left fighting a losing battle while the elite look forward to a new Champions League tailored to their specific needs.

UEFA will, of course, battle to ensure that the tournament remains open to everyone, but the economic disparity it would perpetuate by ceding to the clubs' principal demands will effectively close the Champions League's doors to all but a select few.

The Champions League would, thus, become an illusion itself; a European Super League in everything but name.