That England is now producing

The target back in 1997 when Howard Wilkinson became the FA’s first Technical Director was to establish “an Oxford and Cambridge” level of footballing education in England. With a coherent plan and the right coaches, the future for the nation's young players would now appear to be secure.

Gareth Southgate’s senior squad – set for Euro 2020 qualification matches over the coming days – has been replenished with new players from the youth sectors. England sent the third-youngest squad by average age to the World Cup in Russia last summer and the manager has also given senior caps to nine players aged 21 or under in the last 18 months.

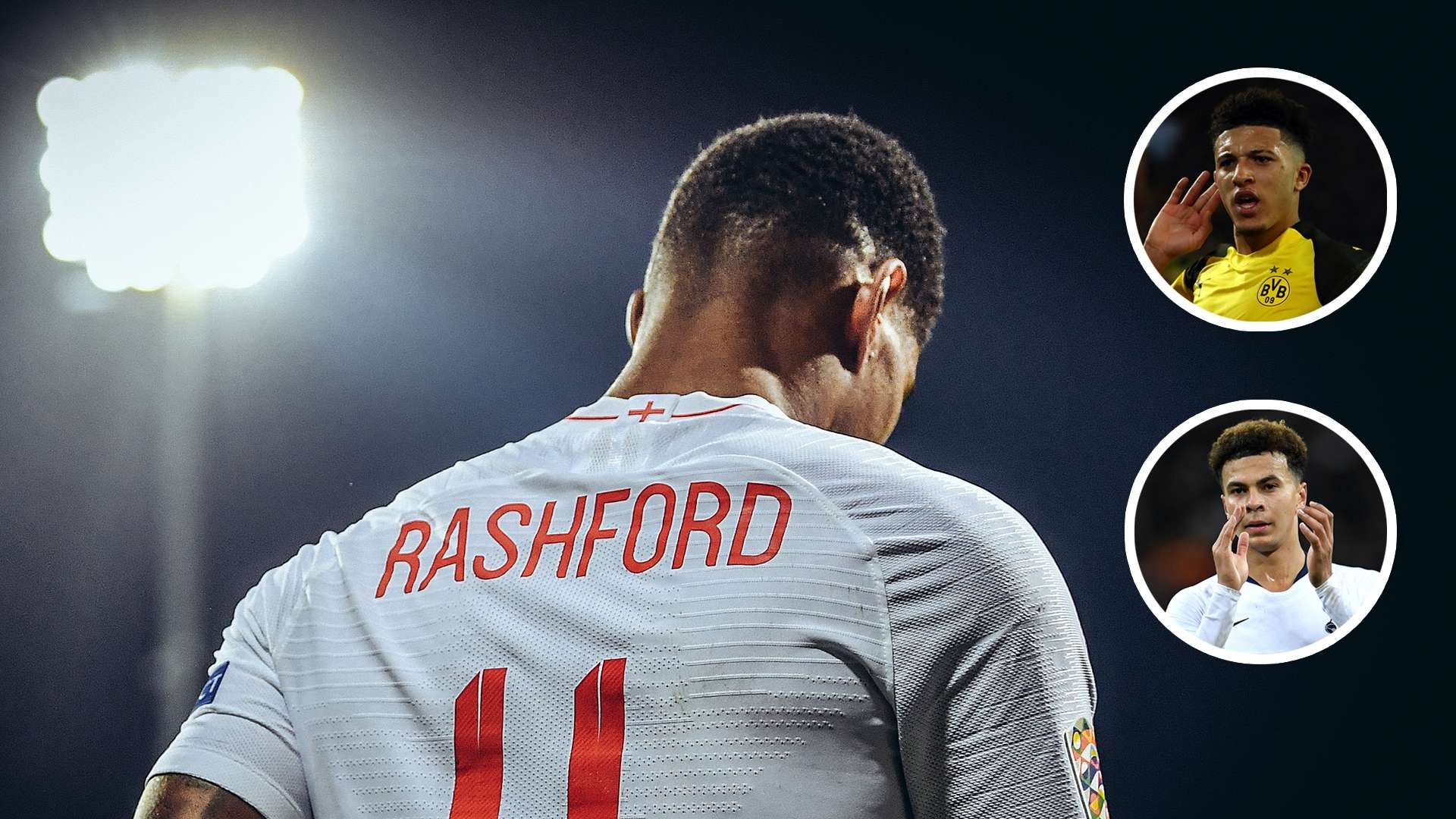

Among those are Goal’s 2019 NxGN winner Jadon Sancho, starring in the Bundesliga for Borussia Dortmund having left the Manchester City

Sancho – along with established young stars like Dele Alli, Marcus Rashford and Trent Alexander-Arnold – should be national team mainstays for the next decade, as well as regulars for clubs at the sharp end of the Premier League and Champions League.

“When I went to the FA, I went with a view that youth development could be dramatically improved,” Wilkinson tells Goal of his appointment.

He had achieved success with Leeds – he remains the last Englishman to win the top-flight title as manager – and was integral in setting up the famous Leeds academy which turned out the likes of Gary Speed, David Batty and Harry Kewell, and continues to this day to produce

“When I joined Leeds, they had already signed 18 schoolboys, of which

“Five of them featured for Leeds and, indeed, were part of the squad for the [2001] Champions League semi-final.”

Using his experience with Leeds, Wilkinson and the expert team that had been assembled at the FA set about transforming how youths are brought through for the national teams.

“As a

“It wasn’t just me. There’s a lot of significant people along the road there.

“Myself, Robin Russell, Les Reed, John McDermott – one of the best youth developers in Britain if not Europe. I had an immensely talented squad working with me.”

Wilkinson wanted to share the idea with new England players – and everyone involved in the development of young talent – that those representing the national team would be embarking on an international career path that could complement the one they would hopefully go on to enjoy with their clubs.

“What I wanted, and what we created, was a pathway whereby there was consistency in what we did with the players,” he says.

“If we identified the best players in England at 15, we wanted those players to have a parallel development.

“I used to tell them, 'You’ve got two career paths now. You’ve got the career path in professional football at club level and you’ve got a career path in international football, and the two are interconnected. If you do well in one, you’re going to do well with the other.'"

Getty Images

Getty Images

Key to that has been a joined-up way of thinking across all age groups in the national teams, with a clearly-outlined approach to coaching and playing that would be implemented at all levels.

“There are major differences; the number of days you’re in the England setup and the number of days you’re with your club, and the amount of time you have

“It’s important that if we identify them at 15, they start learning. It shouldn’t be as it used to be: I’m playing with the 18s, I’m now in the 21s – they’ve got a different manager and he’s doing it his way.

“The coaches have got to be themselves, but they have got to do it the England way.”

Among Wilkinson’s proposals was a plan to create a national football centre, which could serve as a headquarters for teaching and learning. St George’s Park was eventually inaugurated by the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge in 2012 and opened in 2013, much later than originally scheduled.

“It was a comprehensive strategy, but we needed a symbolic heart,” he says. “We needed a home. I said I wanted it to be the Oxford and Cambridge of English football; it was essential to the whole plan.

“I identified the site of St George’s Park. In 2002, we started laying the pitches and then, all of a sudden, I left in 2002 and, in 2003, the eye was taken off the ball. St George’s Park was mothballed, the new Wembley was initiated and the cost of the new Wembley ballooned.

“It wasn’t until 2008 that St George’s Park and all that it stood for got back onto the agenda and it was only narrowly voted through. Then, it opened in 2013. Instead of opening in 2002 or 2003.

“The whole saga – will we have St George’s Park or won’t we? – was overtaken by the need to build a new Wembley, whose cost tripled. We paid a heavy price for that.”

Getty Images

Getty Images

France’s pre-eminence in youth development has been long-established and its centre of excellence at Clairefontaine has been regarded as the gold standard. England has now got one of its own; St George’s Park has 13 pitches,

Without the plan set in place back in 1997, though, St George’s Park would be just another estate. What makes it effective is the plan underpinning it.

“St George’s Park was important because it was a hub; it was symbolic,” he says. “You can’t have any sort of organisation if you haven’t got a place that is home.

“What matters more than the symbolism is the plan. That’s what’s crucial – the plan – and making sure it’s implemented properly.”

The establishment of the UEFA Pro Licence coaching badge and the FA Charter Standard Awards for clubs at grassroots levels – these count among the developments in English football over the past two decades which are now in evidence in the performance of the national teams.

“It was a raft of proposals which I took to the FA and developed,” he says. “And they accepted it.

“It was football academies

“And, obviously, the development strategies for the national men’s and women’s national teams. That was important. I appointed Hope Powell as the first full-time England coach for the ladies.

“So, it wouldn’t have been possible without a comprehensive plan.

“Take it from me, you don’t get a good school unless you’ve got good teachers. And you don’t get a good school if you haven’t got good leaders and a good head. What we have now is good teachers.

“The basics have got to be there. And as that child goes through the school developing, the learning pathway has got to be as good as it can be and appropriate to the objectives.

"The learning pathway as far as the England players are concerned, is one which is coherent and cohesive.”

Getty Images

Getty Images

Wilkinson credits the involvement of Dan Ashworth – appointed the FA’s Director of Elite Development in 2012 and one of the authors of the much-vaunted 'England DNA' programme – as one of the key men behind the project’s revival.

“Thankfully, Dan took the baton,” he says.

“When St George’s Park was mothballed, the plan was not quite put on hold but the plan was slowed down dramatically.

“The proposal to restart in 2008 was only narrowly agreed by the FA council. It wasn’t as if it was a landslide. Fortunately, we are now back on track.”

While trophies may not usually be thought of as the be-all and end-all in youth football, Wilkinson is content to use them as proof that the methods set in place are now paying off.

In a similar vein, the senior men’s team’s performances in Russia last summer – where they progressed to the World Cup semi-finals for the first time in 28 years – should provide plenty of confidence for the players to believe that England is on the right path.

“At the moment – from under-17 up to under-21 – we’re top of the world rankings,” he says. It is telling – also – that three of the top four in Goal’s NxGn ranking of the best teenage talent in world football are English.

“Trophies are important because they

“What Gareth did in Moscow was immense, getting us to where we were. What the players who are now in the England setup know is we’ve been there, seen it, done it.

“That’s

Germany's recent struggles at club and international level demonstrate that even the best-laid plans can go awry. That is why the FA is looking to safeguard against future malfunctions.

“The quality and quantity of coach education from grassroots right through to pro level is first class,” Wilkinson says.

“Can it be improved? Things can always be improved.

“If you’ve got good leadership in any organisation, it will always be guarding against complacency. It will always be asking the question: 'What can we do better?'”

It is one reason why, in Wilkinson’s opinion, Southgate is the ideal candidate to head up the team and bring through the talents when the time is right.

“Gareth’s been in it with the under-21s,” he says. “He’s steeped in it. Now he’s in it with the England team. He’ll give you chapter and verse on what the learning programmes are, how they are being constantly investigated and developed.”

With the explosion of the Premier League, it has meant that elite young footballers are potentially getting fewer and fewer chances in the first team at top English clubs. To that

“Late 90s, just past 2000, England was becoming a finishing school for French players,” he says. “They were getting schooled in France until they were 18 and then English clubs were buying them and bringing them here. They were testing their mettle in our league.

“Now, it’s almost gone the other way. We’re changing perception. The fact that we’ve got kids schooled in England playing in the Bundesliga is enormous. The Bundesliga is a strong league.”

And it all provides the proof that England's youth development can now be regarded as the best in the world.