It was an act that shook South American football to its core and, 30 years to the day, now occupies its part in the continent's rich sporting folklore. Chile's own Maracanazo has gone down in legend, with the man at the centre of the scandal still renowned as a national anti-hero.

Roberto Rojas was perhaps the finest goalkeeper ever to represent the Roja. Nicknamed 'The Condor' for his startling ability to fly across the net, he was the undisputed Chile No.1 for almost the entirety of the 1980s, playing in three consecutive Copas America over the course of that decade and racking up 49 caps. At club level, he starred first in his home nation with Colo Colo and later at Brazilian giants Sao Paulo.

Controversy, however, seemed to stalk Rojas throughout his career. In 1979, the 21-year-old was one of several Chile players included in the country's South American Under-20 Championship team with the help of fake passports issued by collaborating officials in the national Civil Registry.

The Roja 'youngsters' were able to travel to host nation Uruguay and finished third in their group, but the ruse had already been discovered while the tournament was ongoing – ironically, provoked by a complaint filed by Paraguay after Chile themselves had accused their rivals of fielding over-age players.

The entire squad was arrested upon arrival in Santiago, and coach Pedro Garcia later sentenced to 1084 days in prison for his part in organising the scam (FA chief General Enrique Gordon, designated by dictator Augusto Pinochet, was quietly shunted off to the Chilean embassy in Nicaragua and never faced charges).

Five years later, Rojas tested positive for an anabolic steroid following a friendly match between Chile and England, an act that cost him the chance to represent his country in the 1984 Olympic Games.

There were also issues prior to the 1987 Copa, where, as the leader of a players' commission discussing the awarding of prize money with the FA, Rojas' intransigence almost led to the squad returning home without playing a single game, before he was replaced with a more amenable negotiator.

But it was on September 3, 1989 that the goalkeeper's reputation would be tainted forever by a gambit so daring, so dramatic and ill-advised that it could have come straight out of a film script.

Qualification for the 1990 World Cup from CONMEBOL's Group 3 had proved a heated affair. Brazil and Chile were drawn alongside the continent's whipping boys, Venezuela, and each inflicted home and away victories on the Vinotinto. The two games between the top two would essentially decide who went to Italy and who stayed at home.

The first game in Santiago was marked even before kick-off by a public spat between Romario, the new darling of the Selecao, and fractious Chile coach Orlando Aravena.

“I am going to shut Aravena's mouth,” Romario vowed before the game, but the future Barcelona forward was booked before the game started and lasted just three minutes before seeing red for his part in an on-pitch brawl.

Aravena and Chile midfielder Raul Ormeno were also sent off in a brutal 1-1 draw. “It was not a game, it was a war,” Chilean sports newspaper Futbol Total lamented in its report the following day.

But it was a result that nevertheless left the single qualification spot in Group 3 up for grabs: Brazil and Chile went on to smash Venezuela in consecutive games, meaning the Selecao led by virtue of goal difference going into the final match in Rio de Janeiro's Maracana. A win for Chile would take them to the World Cup.

In fact, the Maracanazo of September 3, 1989 brought together two unlikely co-protagonists. Rojas we have already met. But up in the stands of the Maracana was a pretty Rio native in her early 20s named Rosenery Mello. She and 141,000 fellow spectators watched as Careca fired Brazil 1-0 ahead at the start of the second half, leaving the Selecao on the verge of qualifying.

Rojas had been in fine form during the first half, making several key saves to keep Brazil at bay. But his antics in the net, time-wasting and holding onto the ball in an attempt to take the sting out of the fearsome home attack, had not endeared the goalkeeper to the Maracana crowd. Finally, after 67 minutes while Claudio Taffarel fired a goal kick back up-field, a flare flew from the terracing behind the Chile goal and the player fell to the ground.

The next few minutes were pure chaos. Chile's physiotherapist Alejandro Koch and most of the line-up rushed to attend to their stricken captain, although Patricio Yanez found time to gesture towards the stand grabbing his testicles – a move that is now known locally as 'doing a Pato Yanez'.

When the smoke cleared and Rojas emerged from the scrum of players and officials his face was streaming with blood; alleging that the flare had caused the damage, the Roja left the field and took refuge in the dressing room for three hours while preparing an official protest to FIFA and CONMEBOL.

Chilean hopes that the incident could overturn the result, however, were short-lived. Thanks to the images captured by Argentine photographer Ricardo Alfieri, it was soon discovered that, while a flare was thrown, it had landed on the playing surface without touching Rojas' person. Rio police were also able to identify the Maracana aggressor, none other than the 24-year-old Mello.

“I took a sequence of 14 or 15 photos of the flare falling and the rest, because the flare landed on the floor and threw up a cloud of smoke,” Alfieri – who at that point had almost 20 years of top-level experience as a photographer for El Gráfico magazine and who was working at the game for a Japanese publication – told Goal.

“Rojas went down amidst the smoke and after that the next photo I have of Rojas, he was covered in blood. I had the impression that it had not hit him, but there was a contradiction: it didn't hit him but the guy was bleeding. It didn't make sense... This was 1989, you couldn't imagine a professional sportsman would play a game with a blade hidden in his glove!”

"I was terrorised," Brazil captain Ricardo Gomes recalled years later to CNN. "I thought immediately of losing the chance to go to the World Cup. It was something really bad.

"Now, of course, with all the cameras on mobile phones around, it would have been impossible.”

While Brazilian journalists besieged the Chile dressing room in an attempt to get the truth, word soon escaped that, of 200 photographers in the Maracana, not to mention the television cameras, Alfieri was the only person who had captured the moment the flare hit the ground. Brazilian Football Confederation (CBF) chief Ricardo Teixeira, running the risk of seeing his team disqualified from the World Cup, was not inactive.

“I was sat there in the stadium and three guys were sent to get me, three basketball players about seven feet tall,” Alfieri added. “They were three security guards because I was wanted in the Maracana's VIP box. I could see then I was in a real mess, I thought more images were going to come out.

“I went upstairs and told my story, what really happened, but to see the reality we had to develop the photos. They couldn't be developed just anywhere, only in professional studios. They asked me if I could develop them and I just wanted to go back to Buenos Aires, I could see I was in a mess that was not of my own making. They got permission to develop them in a publishing house, we went there and there was the photo of the flare.

“Up to that point when the photo was developed, Chile were going to the World Cup, Brazil were going to be eliminated."

The immediate upshot of the 'Maracanazo' was the awarding of a walkover 2-0 victory to Brazil, sending them to Italia 90. In December 1989 a FIFA disciplinary committee additionally handed out lifetime bans to Rojas, Aravena, vice-captain Fernando Astengo and several other Chile officials, including Koch.

The nation itself was also banned from taking part in qualification for the next World Cup in 1994. It was not until the following year, however, that the goalkeeper finally came clean over the subterfuge.

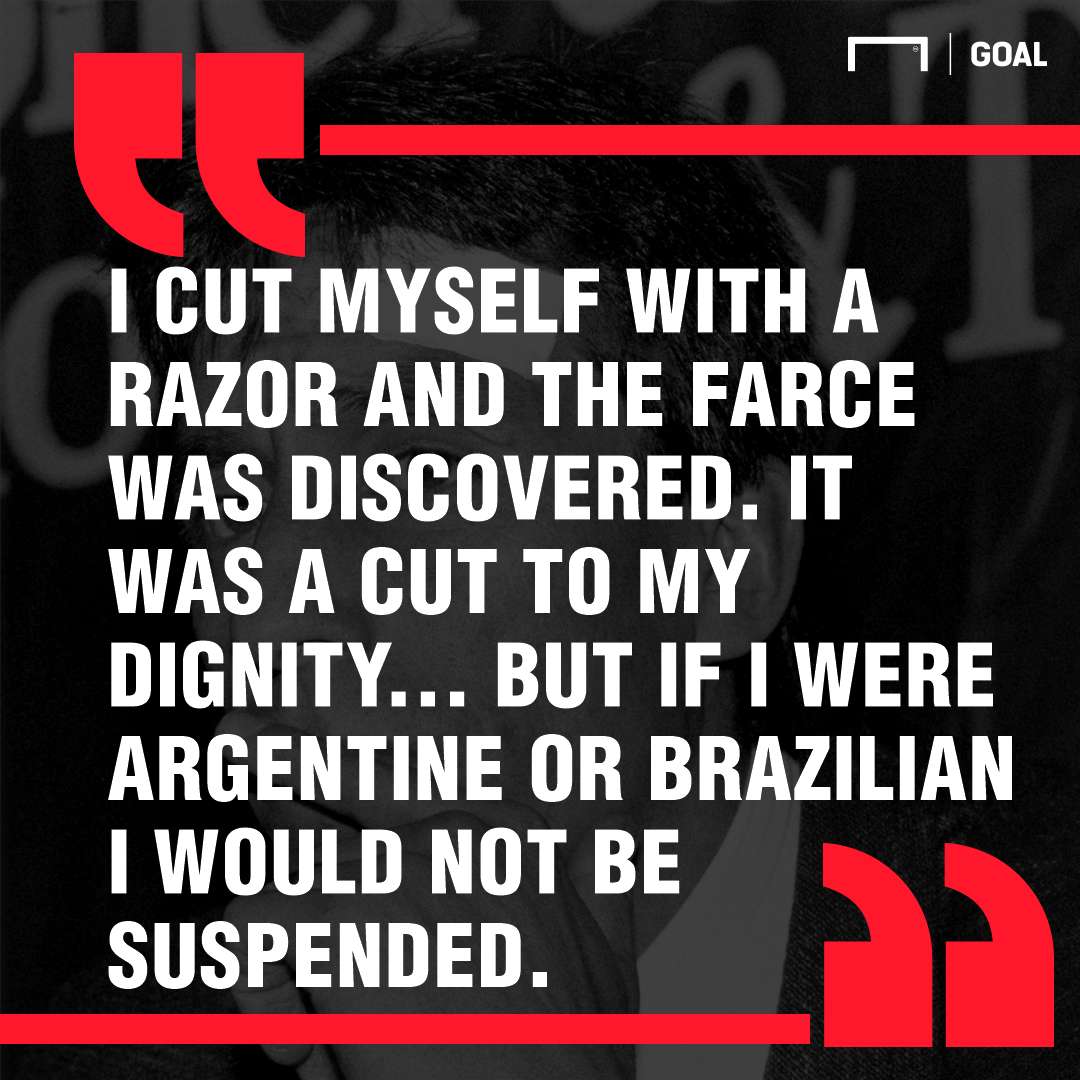

“I cut myself with a razor and the farce was discovered,” he explained in a sensational interview with La Tercera, who ran the story on the front page under the headline 'I'm Guilty!', revealing how with the aid of Koch he had smuggled the blade onto the pitch inside his glove.

“It was a cut to my dignity. I have had problems at home with my wife, my team-mates turned their backs on me... but if I were Argentine, Uruguayan or Brazilian, I would not be suspended.”

Rojas added in a later interview with Mas Vale Tarde: “[I did it] for passion, for Chile to have a chance because Chile was being harmed at that time. We had had problems in the last qualifiers, but when one makes that kind of mistake he wants the chance to redeem himself, but I did not have that.”

Mello, meanwhile, became a minor celebrity in Brazil for her part in the Maracanazo, even posing on the front cover of Brazilian Playboy in November 1989. Those 15 minutes of fame allowed 'The Maracana Firecracker', as she was dubbed, to live comfortably until the money ran out and she was forced to return to Rio, living with her brother and, as legend has it, selling fireworks. She passed away after suffering a brain aneurysm in 2011, aged just 45.

The Maracanazo scandal incredibly did not affect Rojas' standing in Brazil. In 1994, he was hired by Sao Paulo as the club's goalkeeping coach, where he took under his wing young Rogerio Ceni. The pair worked together for almost a decade as Ceni became a Tricolor icon, among other achievements setting the record as the highest-scoring keeper in football history – a feat he ascribes in part to the Chilean.

“I remember that he always insisted I should not just be content with saving the ball. That I had to work with my feet a lot,” the Brazilian recalled to La Tercera. “I played more than 400 games with him. He was a person that had huge influence in my development.”

“I felt sorry for Rojas with the suspension because he was a tremendous goalkeeper, a great goalkeeper,” Alfieri stated. “He was a terrific sportsman and because of one photo, he got suspended. But all I did was fulfil my journalistic mission and as a photographer.

“Luckily for me, unluckily for Chile, I was able to take that photo because otherwise Brazil wouldn't have gone to the World Cup and Chile would have.”

Rojas' lifetime ban was rescinded in 2000 in a FIFA amnesty and he went on to coach Sao Paulo and Sport Recife among other clubs before swapping the bench for television studios as one of Chile's most respected pundits, despite a prolonged battle against Hepatitis C – “I saw myself in a coffin”, he told UOL Esportes – that was eventually overcome thanks to a liver transplant.

But it was that fateful September afternoon in Rio that sealed his place in football infamy. A goalkeeper willing to break all the rules to help his country reach the promised land; a flare-wielding Playboy model; a photographer strong-armed into revealing the truth and save Brazil's World Cup hopes; a scandal that reached across two nations and an entire continent: not even the most absurd fiction could hope to replicate the amazing story of Chile's Maracanazo.