Diego Maradona went into the 1990 World Cup as the planet's premier footballer, almost without peer.

The Argentina star's dazzling performances on the way to the title four years earlier in Mexico, coupled with the magic he weaved to turn Napoli from Serie A also-rans to champions of Italy for the first time in the club's history, meant his status as an all-time great was already secure.

Indeed, just a month prior to kick-off in Italia 90, Napoli had again won the Scudetto, Diego's 16 goals placing him just behind Marco van Basten and Roberto Baggio as the league's top marksman.

Once the action began, though, it was Maradona's heart that led the Albiceleste. The talent was still there in flashes, of course, most notably in his outrageous dribble and pass that set up Claudio Caniggia to score the only goal of a tense last-16 tie against Brazil – a strike that ranks right alongside his 'goal of the century' to down England.

However, he was hobbled by an ankle injury that needed constant painkilling injections and swelled up roughly to the size of a grapefruit. Consequently, neither Argentina's captain nor the team itself could produce their best football.

Carlos Bilardo's men nevertheless continued to slog, hack and grouse their way through each round, their enviable team spirit and intensity compensating for the lack of finesse, until only hosts Italy stood between the nation and a third final in four World Cup appearances.

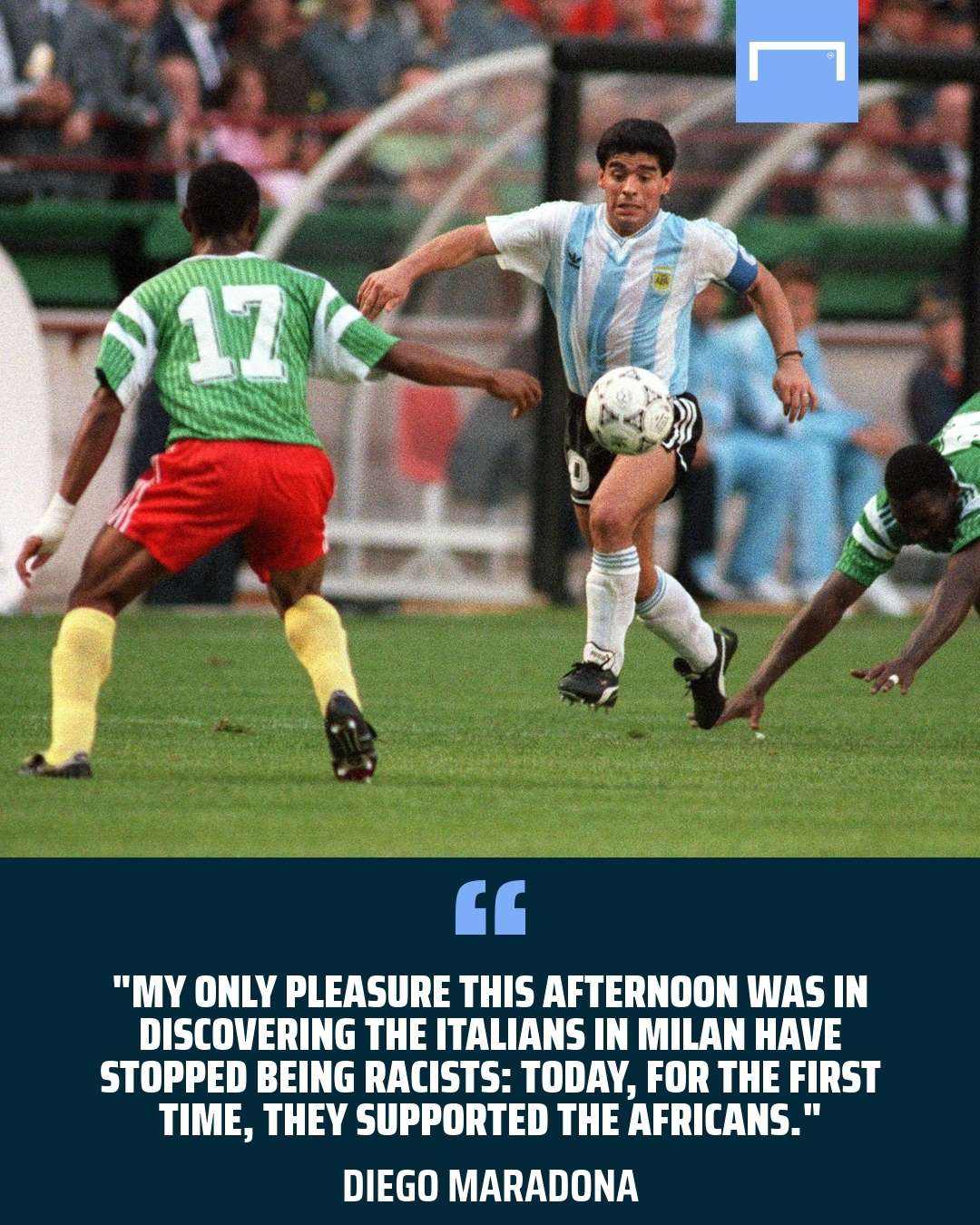

Despite Diego's position as Napoli's talisman – or perhaps because it – the Italian crowds gave Argentina a torrid reception during their stay. Prior to their first group match against Cameroon, the nation's anthem was roundly booed and whistled by the San Siro – a portent of what would prove a catastrophic afternoon for the World Cup holders as they were humbled in a 1-0 defeat.

Fuming after the final whistle, Maradona did not mince his words.

“My only pleasure this afternoon was in discovering the Italians in Milan have stopped being racists: today, for the first time, they supported the Africans,” he fired to reporters.

Getty/Goal

Getty/Goal

Bilardo, meanwhile, brought his shell-shocked charges together and calmly laid out their options: either they make it to the final, or else pray that the plane taking them home to Buenos Aires fall into the ocean.

Fortunately for all involved, they opted for the former.

In the second group game against the Soviet Union, Diego pulled off his second, less heralded 'Hand of God', palming a header off the line to save a certain goal with the game poised at 0-0. Nery Pumpido, who had committed a hideous error to allow Cameroon to score in the opener, compounded his rotten fortunes by suffering a double leg fracture in a seemingly innocuous clash with defender Julio Olarticoechea.

Sergio Goycochea was thrown into the action, and kept a clean sheet as Pedro Troglio and Julio Burruchaga struck to down the Soviets in their last-ever World Cup.

A subsequent draw against Romania was enough to send the Albiceleste into the last-16 as one of the best third-placed sides, but it was not until Maradona and Caniggia combined to end Brazil's hopes that Argentina really looked like making an impact on the tournament.

Next up were Yugoslavia, who with the likes of Dragan Stojkovic, Robert Prosinecki, Zlatko Vukovic and the young talents of Dejan Savicevic and Robert Jarni, were one of the dark horses to take the title.

Neither side could break the deadlock over 120 minutes of football and in the subsequent shoot-out Maradona fluffed his lines with a kick that would have put Argentina 3-1 ahead.

“Take it easy, monster,” Goycochea consoled his captain, “I'm going to save two more.” The keeper was as good as his word, denying both Dragoljub Brnovic and Faruk Hadzibegic to send Argentina to the semis.

This would not be just another game for Diego, though. As well as the pressure of a World Cup semi-final, he had his own personal vendetta to pursue against Italy; and the stage, as fate would have it, would be none other than his adopted home at the Stadio San Paolo.

The affection between Maradona and Napoli has always run far deeper than mere footballing matters.

As the son of migrants from Argentina's vast, impoverished interior region who settled in Villa Fiorito – one of the countless shanty towns on the periphery of Buenos Aires where the sewers are open and fetid, the roads earthen and on rainy days torrents of garbage would flow through the streets – Diego understood from an early age what it meant to be discriminated against and mocked by the capital's middle and upper classes.

Upon arriving in Naples, he instantly identified with the racism suffered by the southern Italian club at the hands of its northern neighbours.

“Welcome to Italy,” fans of Milan, Juventus, Genoa or, as on his 1984 debut, Verona would proclaim when Napoli came to visit. “It was north against south, the racists against the poor,” he recalled to journalist Daniel Arcucci.

So, Maradona's heroics in taking Napoli from the foot of Serie A to the summit were not just felt on the football field; he is credited with installing new pride to a city resigned to the jeers and insults of their wealthier neighbours.

Diego could be certain, then, that on at least one occasion in the World Cup Argentina's anthem would not be disrespected. But, typically for the outspoken No. 10, he wanted even more.

“The Neapolitans are being asked to be Italians for one night, while the other 364 days of the year they get called terroni (an Italian slur roughly translated as peasants),” he told reporters.

“I only want respect for the Neapolitans, both my team-mates and I know they are Italians, we cannot ask for them to cheer for us, but the rest of Italy should know the people of Naples are just as Italian as they are.”

While Diego did not fully sway the hearts of all the 60,000 in attendance at San Paolo on July 3, 1990, he did provoke divided loyalties.

“Maradona, Naples loves you but Italy is our homeland,” one banner read, while another professed: “Diego in our hearts, Italy in our songs.” The Albiceleste captain received a rousing ovation when he ran out on the field and for the first – and last – time the Argentine anthem rang out largely absent of interruptions.

The game itself again proved a battle of attrition rather than fluent football. Toto Schillaci fired Italy ahead after 11 minutes, only for Caniggia to strike in the second half, rising above Walter Zenga to nod home the equaliser.

Argentina headed once more for penalties, where Goycochea repeated his heroics in saving the last two Italy efforts to send Argentina to the final.

“It affected us,” Zenga later told the National. “It’s hard to explain in five or so words, but we came from Rome where we played five games, with five wins and no goals against. The whole stadium did not care whether they were Roma fans, Lazio fans, Inter fans or Juventus fans. It was complete support, all 90 minutes.

"Then we arrive in Naples, Maradona says a few things, and the atmosphere changed. We cannot look at that as an excuse for Argentina beating us, but the feeling before was different. It surprised us, but it didn’t cause us to lose.”

If Maradona had achieved a measure of revenge for his perceived ill-treatment at the hands of Italy, the Azzurri fans were preparing to make him pay for his transgressions ten-fold. The build-up to the final was marked by tensions between Argentina and their hosts, with Diego clashing with Italian authorities when his brother Lalo was pulled over having borrowed his Ferrari, an episode that even drew in the nation's ambassador Carlos Ruckauf.

Tempers were further inflamed by accusations that an unidentified Italy fan had vandalised the Argentina flag at Roma's Trigoria training base.

Five days later, Rome's Stadio Olimpico exploded in jeers and cat-calls as Argentina walked out to face West Germany in the final, with the anthem barely audible over a wall of jeers.

As his team-mates attempted to fight through the noise and make their voices heard, RAI's camera panned to the seething Diego, slowly eyeing up each corner of the stadium and mouthing repeatedly, “ hijos de puta, hijos de puta” (sons of whores) to the hostile crowd.

Getty

Getty

Argentina did not shy away from the fight, in the most literal of senses, losing both Pedro Monzón and Gustavo Dezotti to red cards over the 90 minutes.

Andreas Brehme ultimately went on to seal the Europeans' victory from the penalty spot late in the second half, earning Mexican referee Edgardo Codesal a lifelong place in Maradona's voluminous enemy's list in the process for 'robbing' Argentina of the World Cup on the behest of his hosts.

“This must be a town of thieves,” he sneered in 2018 when informed by reporters that his Dorados team were visiting Codesal's adopted hometown of Queretaro. The Uruguayan-born official did not hold back in his response, labelling Maradona “one of the worst people I have ever met in my life, disgusting” in an interview with Radio 1010 .

“I want to be the idol of the poor kids of Naples, because they are just like me as a youngster in Villa Fiorito,” Diego is said to have proclaimed upon arriving in the city for the first time in 1984. For all his misdemeanours and flaws, nobody can deny that the Argentine succeeded in his mission.

Almost three decades since he last lined up for Napoli – his time in Italy ended less than a year after the World Cup when he tested positive for cocaine following a clash against Bari – he still casts a spell over the city, whose graffitied walls betray his spiritual presence at almost every turn.

He may not have turned the boisterous masses of San Paolo into Argentines, but with his talents and sympathies for the city's struggle to get a fair deal from the rest of Italy, Diego without a doubt became its favourite son, a Neapolitan in every possible sense.